There is a lot of concern among farmers about dry spring conditions as we head into the 2022 growing season. Significant areas of the western U.S. are encountering extreme to exceptional drought. In the Midwest, the southern tiers of Wisconsin counties and the northern 1-2 tiers of Illinois counties are abnormally dry or under moderate drought.

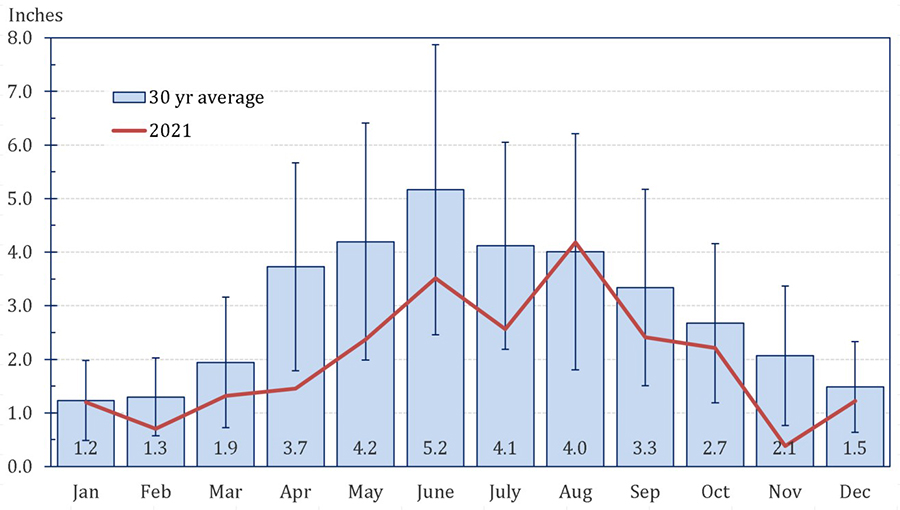

Figure 1 describes the 30 yr monthly average precipitation at the UW Agricultural Research Station in Arlington. Only 23.5 inches of precipitation was measured during 2021 compared to the 30-yr annual average of 35.2 inches. We typically get most of our precipitation during April, May and June. The variability (risk) of precipitation patterns during April to June is quite high ranging from 3.8 to 5.4 inches (standard deviation= + 1.9 to 2.7 inches). Monthly precipitation amounts can range from 1.8 to 7.9 inches of precipitation during April, May and June.

Figure 1. Monthly precipitation at the UW-ARS in Arlington. Data were derived from the Midwest Regional Climatological Center. Error bars are the standard deviation of the 30 yr monthly average. |

During 2021, monthly precipitation was outside of the error bars in Figure 1 only during April and November. Drier conditions during April allowed for early planting, while drier grain moisture was observed at harvest. The month that was average for precipitation was August which is the grain-filling period for corn. No 2021 precipitation monthly average was above the 30 yr monthly average. So even though precipitation was one of the lowest on record, the distribution was adequate for near-record grain yields.

Some of the current drought conditions described by the U.S. Drought Monitor for Wisconsin and Illinois are a holdover from the 2021 season. Since January 2022, the amount of precipitation measured at Arlington is average. Soil profile water content is likely lower than normal.

How Do We Prepare for the 2022 Growing Season?

The short answer is that you “manage for the average.” Don’t change things too much unless you have been considering and preparing changes in your management style for some time. The weather during 2022 could be cooler/warmer and/or drier/wetter than normal.

Again, I would “manage for the average” during 2022. No one can predict the weather. If you are convinced that the weather is going to be drier than normal, then I would consider the following:

- Select a hybrid that is bio-engineered to include drought “tolerant” transgenes. Be wary of hybrids traditionally bred for drought “resistant” traits.

- Use hybrids with the Bt-ECB bio-engineered trait. Stalk integrity will be important for water molecule movement within the plant and will likely increase standability at harvest. Often mycotoxin issues are more often observed in drought stressed years because of increased corn borer activity.

- Select a hybrid that is shorter-season than typical for your field. You will give up yield compared to a full-season hybrid, but the the shorter-season hybrid will go through pollination earlier when soil profile water might be adequate to ensure pollination.

- Plant early. Planting corn early has the same effect as selecting a shorter-season hybrid. Plants will go through the pollination phase earlier when soil profile water content is greater.

- Lower plant population. Our data shows that grain yield is not affected by plant population during a drought year. By lowering your plant population you capture some return on investment by lowering seed cost.

- Rotate your crops. Rotated corn grain yield during a drought year is increased (25 to 30%) more than continuous corn.

- Use no-tillage. Residue on the soil surface acts as a mulch and a boundary layer for evaporation from the soil surface.

- Control weeds. Weeds will compete with corn for water resources.

- Do not over-apply nitrogen. Apply at MRTN rates. Nitrogen increases corn leaf area thereby increasing the potential amount of surface area and cooling load that the plant requires for transpiration.

Some of these management decision changes have the potential to leave yield in the field during a normal weather year. As we saw during 2021, some of these decisions are about timing of precipitation events. I remember the 2005 and 2012 when weather conditions were dry through mid-July. Adequate rains came in mid-July and soils that had higher soil water content allowed plants to escape drought effects on pollination. For some, early planting date and shorter-season hybrids did not work and fields were abandoned.

Joe Lauer

University of Wisconsin